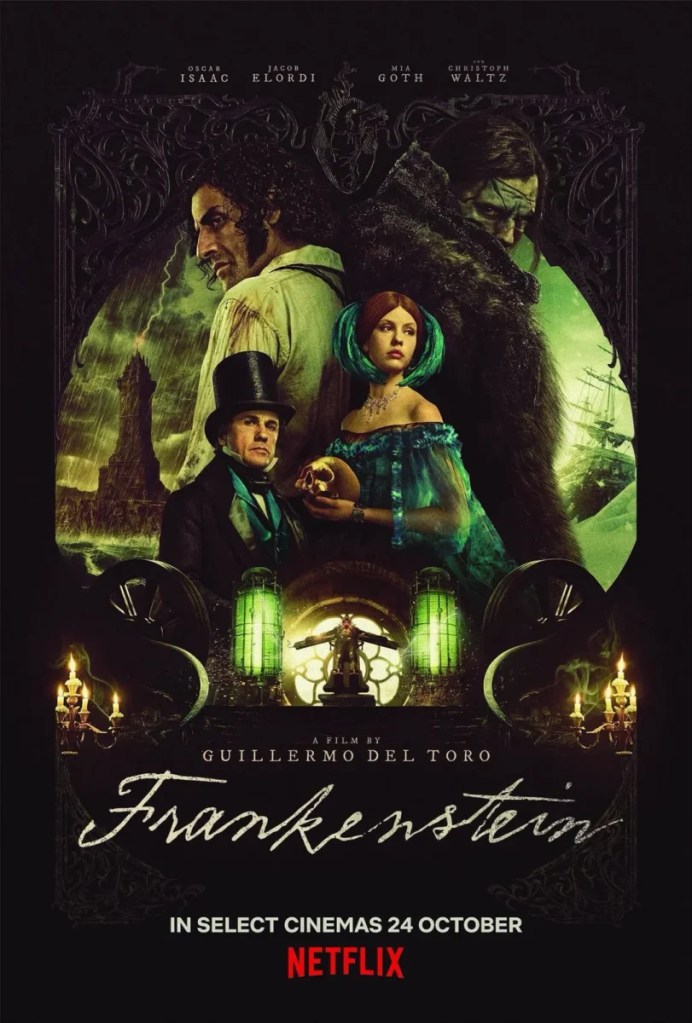

Published in 1818, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, is among the most famous works of gothic horror and science fiction. It shouldn’t be a surprise, therefore, that it has inspired many adaptations, recently, Guillermo del Toro’s film, Frankenstein (2025). What makes del Toro’s portrayal so particularly interesting? Guillermo del Toro’s depiction of Marry Shelley’s Frankenstein explores the beauty of nature’s mysteries, while warning against man’s hubris to transcend nature. This theme is emphasized by many Greek undertones, as well as del Toro’s use of color. His screen adaptation reconstructs the Romantic concept of nature in a horrific light, and revisions the earth through the Creature’s tragic evolution—or rather, devolution.

“The world was to me a secret which I desired to divine” – Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Del Toro accomplishes the first goal through isolation of the Arctic, the damage of family trauma, Harlander’s desperation, and most of all, through Victor’s ambition. The second goal is accomplished through Elizabeth’s defiance and the Creature’s experience with the blind man and his creator. Despite this horrific reinvention, del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025) is hopeful, as revealed through Elizebeth’s relationship with the Creature, and the film’s concluding scene.

The director, Guillermo del Toro, is a Mexican filmmaker who has been in the industry since the 80s but has recently made a name for himself through Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Crimson Peak (2015), and The Shape of Water (2017). These works all share a number of themes from tension between life and death, to labeling the misunderstood as monsters, and of course, the mysteries of nature. These themes are also prevalent in the Gothic literary structure, which del Toro reworks “and adapts…into visual forms” in order to “recreate the feelings” of the gothic stories that fascinated del Toro as a child” (Weeber, 116; Roche, 85). Del Toro’s love of the Gothic genre stems from his pride in his own origin. He comes from a religious background, and loves the gothic representations of divinity. Furthermore, he started with nothing and “through hard work and integrity, achieved greatness” (Roche, 91). This background coupled with his creativity and passion has won Guillermo del Toro three academy awards, and provided him the bandwidth to experiment and take on challenges.

There is no better challenge than Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The novel is a frame narrative, telling the story of inventor, Victor Frankenstein, through letters that a ship captain, Robert Walton, writes to his sister. The inventor tells Walton his cautionary tale of creating a Creature out of corpses, and bringing it to life, only to reject it. As a result, the Creature takes revenge on its creator, destroying his perfect family. In del Toro’s adaptation, Victor does not have a perfect family, but rather, his family trauma is the source of his desire to defeat death. Furthermore, Victor’s love interest in the book, Elizabeth, is his adopted sister, whereas in the film, it’s his brother’s fiancé. Despite these differences, Frankenstein (2025) perfectly captures Mary Shelley’s depiction of nature’s mysteries and the dangers of hubris.

The film opens in lifeless ice, clues the audience into the character’s states while hinting at the consequences of transcendence. The camera pans down to showcase “Farthermost North, 1857” as a captain and his crew are attempting to break through the ice, attempting to traverse the Arctic (del Toro, prelude). The setting of a white and blue expanse of earth, sky, and sea, immediately transports the audience to an alien world. As stark of a contrast as this is to the rest of the story, it is very fitting, firstly, because when Victor Frankenstein’s character—played by Oscar Issac—is introduced, he is just as isolated as his surroundings, and secondly, because del Toro will return the audience to this setting over and over as the story progresses. This technique not only illustrates Mary Shelley’s frame narrative, but it also reveals “the mysterious forces of nature,” specifically that the “pursuit of life is connected to death, and death to the seemingly lifeless matter of the Arctic nature.” (Berg, 4). This cycle of nature is fundamental to the horrific perspective on transcendence, as breaking it leaves one in the Arctic, lifeless and isolated.

Frankenstein’s hubris begins with a traumatic childhood. As Victor tells his tale, he projects his guilt onto others, blaming everyone but himself, starting with his father. When his father was home, “the entire household bent to his will” but Victor says that “the rest of the time, Mother was mine” (del Toro, pt. 1). Despite the short amount of screen time occupied by Victor’s relationship with his mother, cast as Mia Goth, it is clear that he has a possessive desire for her, resulting in an Oedipus complex. He considers her a part of himself, and it is this obsession that makes her death so impactful as “She who was life… was now death. Her eyes extinguished, her smile feeding the cold earth” (del Toro, pt. 1). He blames his father for her death, which then motivates Victor to surpass his father in the art of science and conquer death. This motivation is further emphasized by the red of his mother’s wardrobe continuing in the form of Victor’s gloves, used in the act of divining the secrets of the world, and defying them, by stopping the dead from “feeding the cold earth.”

Victor’s ambition is founded in family trauma, but rooted in a desire to transcend nature. Oscar Isaac portrays the character as hot-headed and passionate, insisting “that man may pursue nature to her hiding places and stop death. Not slow it down, but stop it entirely!” (del Toro, pt. 1). This means that he does not merely wish to divine the secrets of the world, but to undo them altogether. Through the funding of Heinrich Harlander, he finds a way to do just that.

Del Toro also uses Harlander to depict Mary Shelley’s many allusions to Prometheus, saying lines such as “Can you contain your fire, Prometheus?” (del Toro, pt. 1). Through this illusion, Frankenstein’s desire to transcend nature is in full effect, as Prometheus is a Greek Titan, the very type of divinity that Frankenstein attempts to become. Unfortunately for Victor, divinity has a cost, and it isn’t long before he feels the eagles pecking at his liver.

The allusions to Greek Mythology continue as Harlander’s character is revealed to be similar to Pandora. After their introduction, Victor visits Harlander, interrupting a photography session. In this brief interaction, Harlander catches his model biting a peach, and chastises her, saying “This is a memento mori…symbol of life and youth, and you bite into it?” (del Toro, pt. 1). This bit of dialogue symbolizes his own hypocritical biting into memento mori, opening Pandora’s box and getting syphilis as a result. Harlander funds Victor’s battle against death, claiming that it is a “privilege to record…process for posterity” but it is later revealed that he hopes Victor will transfer his mind into the Creature, and save him from the consequences of his actions (del Toro, pt. 1). In the end, it is his desperation to defy nature that leads to his demise.

The character of Elizabeth emphasizes beauty’s mysteries while revealing the depth of Victor’s hubris. When she first appears, it is clear that she is Victor’s love interest too. This fact is meant to make the audience uncomfortable, not just because she is betrothed, but because she is played by Mia Goth, the same actress that played Victor’s mother. This manifestation of the Oedipus complex reveals that his obsession with her, just like his obsession with defeating death, stems from the unresolved trauma surrounding his mother’s sudden death.

This isn’t the first time del Toro has used the incest motif, in fact, there are many parallels between Victor and Elizabeth in Frankenstein (2025) and Thomas and Lucille in Crimson Peak (2015). In the article, “Crimson Peak: Guillermo del Toro’s Visual Tribute to Gothic Literature” Weeber described del Toro’s use of the incest motif as exposing “the nature of masculine and feminine identity and the nature of the family that shapes that identity. Central to the treatment of these themes are the problem of sexuality, the relation of sexuality to pleasure and identity” (Weeber, 123). The loss of Victor’s mother at a young age shapes his identity, forming hubris around trauma. It also implies that he does not abide by the laws of nature, long before he brings the Creature to life.

The character of Elizabeth emphasizes beauty’s mysteries while revealing the depth of Victor’s hubris. When she first appears, it is clear that she is Victor’s love interest too. This fact is meant to make the audience uncomfortable, not just because she is betrothed, but because she is played by Mia Goth, the same actress that played Victor’s mother. This manifestation of the Oedipus complex reveals that his obsession with her, just like his obsession with defeating death, stems from the unresolved trauma surrounding his mother’s sudden death. This isn’t the first time del Toro has used the incest motif, in fact, there are many parallels between Victor and Elizabeth in Frankenstein (2025) and Thomas and Lucille in Crimson Peak (2015). In the article, “Crimson Peak: Guillermo del Toro’s Visual Tribute to Gothic Literature” Weeber described del Toro’s use of the incest motif as exposing “the nature of masculine and feminine identity and the nature of the family that shapes that identity. Central to the treatment of these themes are the problem of sexuality, the relation of sexuality to pleasure and identity” (Weeber, 123). The loss of Victor’s mother at a young age shapes his identity, forming hubris around trauma. It also implies that he does not abide by the laws of nature, long before he brings the Creature to life.

Despite her role as his love interest, Elizabeth is the first eagle to pick Victor’s liver. She, more than any other character in the production, represents nature. The first time she speaks, it is in protest of the unnatural manner of war, saying “Men that were fed, cleaned and nursed and schooled into this world by their mothers, only to fall on a battlefield far away, far from those that provoke these tragedies.” (del Toro, pt. 1) This introduction reveals her character to be pure and natural, character traits further emphasized by her wardrobe. In contrast to Victor’s mother and her red clothing, Elizabeth wears greens and blues and whites, symbolizing the natural elements and innocence. Shortly after she meets Victor, they are getting lunch when he asks her what books she has. While Victor assumes its romance, it’s actually books about insects. She says this is because her “interest in science leans towards the smallest things. Moving with nature, perhaps the rhythms of God” (del Toro, pt. 1). The insect is one of del Toro’s favorite depictions, and he often includes them in his films where they “exceed human control in spectacular ways” (Hultgren, 158). Around an hour into the film, Frankenstein confesses his feelings for Elizabeth, but she rejects him. She says that unlike the butterfly, man has choice, “The one gift God granted us” and she chooses William. (del Toro, pt. 1). In this action, Elizabeth is herself an insect, defying Victor’s control.

Victor’s hubris drives him to success, reanimating the dead, but he is too impatient and proud to see what he has actually done.

When the Creature comes to life, Frankenstein is ecstatic. He dotes on the Creature, showing him nature, first through the sunlight, and second through water, excited because “Everything was new to him. Warmth, cold, light, darkness. And I was there to mold him” (del Toro, pt. 1) This innocent start for the Creature paints him as innocent and docile, a symbol of the very natural world he lives in defiance of. That being said, Victor quickly grows impatient with the Creature’s lack of progress—Victor’s limited definition of progress. Faced with disappointment, Victor comes to realize that he “never considered what would come after creation. And having reached the edge of the earth, there was no horizon left. The achievement felt unnatural. Void of meaning” (del Toro, pt. 1). Telling the story while at the edge of the earth, the Arctic, further emphasizes Victor’s mental state, of achieving his goal, but finding emptiness rather than divinity. That being said, his narrow view of nature blinds him, obscuring his perception of the Creature, just as it does with Elizabeth.

In fact, the Creature finds a kindred spirit in Elizabeth, as they both represent the natural world. When she meets the Creature, Elizebeth bonds with him over a piece of nature, “A leaf? For me? Thank you. Isn’t it beautiful?” (del Toro, pt. 1). She is able to see what he is without seeing what he lacks, which is all Victor sees. Once again, colors further enrich the story, as the two characters’ costumes correlate, with Mia Goth in nature’s green and the Creature in innocent’s white. Elizabeth then defends the Creature to Frankenstein, who—due to his limited view of her—accuses her of being attracted to it, proving that he sees Elizabeth only as an object of attraction. This misunderstanding between Victor, his love interest, and his creation proves that he has gone too far in his desire to transcend nature, white Elizabeth and the Creature have embraced the natural world.

The division between Frankenstein and his creation is solidified around the film’s midpoint, the tale is interrupted and the narrator switches from Victor to the Creature. This change transforms the color scheme of the film from reds, blacks, and whites, to greens, blues, and browns, the very same colors associated with the Creature and Elizabeth. This is because, for the first time, the audience is seeing the world through the Creature’s eyes, who, just as in Shelley’s novel, is fascinated with the natural world. Furthermore, the food he eats is all berries, because the Creature’s “vegetarianism is both a sign of community with nature and of his aspiration to be accepted by men…[he] is both utterly natural (made of pieces of other life forms) and unnatural” (Braida, 37). His innocent fascination stands in direct contrast to Victor’s perverse desire to transcend. The Creature respects the natural world, while Victor wishes to subdue it.

In spite of the Creature’s innocent beginning, he is soon forced to evolve. It is not the natural world that threatens him, but man’s nature. The Creature stumbles upon the cottage of a poor French family, and lives in their barn, observing them as months pass. Through observation, he learns to read and talk, and in return for learning from them, he becomes “their invisible guardian. The Spirit of the Forest…for a moment, a brief, brief moment, the world and I were at peace” (del Toro, pt. 2). Here, the Creature’s representation of the natural world and desire to be accepted by man is in full effect, but it doesn’t last long. While he has the good influences of the old blind man, who teaches him to “know you have been harmed, by whom you have been harmed, and choose to let it all fade” (del Toro, pt. 2), this lesson is in stark contrast against the one learned through observation of hunters, that the world will “hunt you and kill you just for being who you are” (del Toro, pt. 2). In these contradictory lessons, del Toro wants the audience to ask themselves how to forgive a world that hates them. This mixture of lessons is only the beginning of the Creature’s forced education.

The second source of the Creature’s devolution begins in search of his origin. Acting on the old man’s encouragement, he returns to the tower where he was brought to life, and sees Victor’s journals, which reveal that he is not “of the same nature as man” (del Toro, pt. 2). Shortly after, his life with the French peasants comes to a violent end as the blind man dies and the Creature is forced to flee while being shot at by the hunters. To his dismay, the Creature heals, feeling “lonelier than ever, because for every man there was but one remedy to all pain: Death, a gift” denied him (del Toro, pt. 2). While his inability to die could be considered a transcendence from nature, as he shares the immortality of divinity, it is not one the Creature achieved, but was instead forced upon him. The Creature didn’t ask for life, and is now forced to endure it alone forever.

Frankenstein’s hubris causes him to reject his creation, which teaches the Creature his final lesson. Rather than accept his fate, the Creature makes one last attempt to obtain companionship. He confronts Franksenestin at his brother’s wedding, requesting that he create another Creature. Victor refuses, fearing procreation, which he calls “death begetting death” (del Toro, pt. 2). Victor has finally come to see his defiance of nature and wishes to stop any further harm, but he fails to realize that it is too late to undo the harm he has caused. His final rejection results in Creature’s final resolve that, and since he cannot have love, he “will indulge in rage,” which, like his life, “is infinite” (del Toro, pt 2). Through this scene, the Creature becomes the second eagle to peck at Victor’s liver, and acts out this resolution by physically attacking Victor. The Creature has learned his final lesson, that while mankind’s acceptance is unattainable, mankind’s violence is offered freely.

Elizabeth is the Creature’s last tie to humanity, bonded to him through nature, and her death cuts his ties. She sees the Creature attacking Victor and intervenes, pacifying the conflict. Unfortunately, Victor’s failure to understand their bond solidifies when he sees them embrace. He grabs a gun and aims for the Creature, but shoots Elizabeth by mistake. The red that once symbolized defying death now soaks into her dress as she bleeds out. The Creature holds Elizabeth as she dies, hearing her final words: “ My place was never in this world. I sought and longed for something I could not quite name. But in you, I found it. To be lost and to be found, that is the lifespan of love… And in its brevity, its tragedy…This has been made eternal” (del Toro, pt 2). In her final dialogue Elizabeth achieves what Victor has attempted all along: transcendence, but she gains it through embracing nature, specifically, her death. Victor’s hypocrisy and hubris finalizes his horrific trance dance as well as the Creature’s devolution.

Only by embracing nature again, are Victor and the Creature able to make amends. In the present arctic setting, the tale comes to an end, and the two characters are able to see their story from a distance. Victor realizes he is dying, and forced to come to terms with his mortality, he is able to see the big picture. Death is necessary, and when he dies, he will become a part of nature. He feels remorse, and pleads with the Creature for forgiveness. Remembering his time with the blind man, the Creature indulges “Victor… I forgive you…Rest now, Father. Perhaps now, we can both be human” (del Toro, pt 2). In the hope that they can both be humans, the Creature is describing a hope that Victor can escape his hubris in death. Similarly, the Creature hopes to forgive mankind for their rejection, and find healing in the isolation of the Arctic, “Created by lifeless nature, he returns to the lifeless, ice” (Berg, 6). Hence why the final shot of the film depicts the Creature in the setting of a white and blue expanse of earth, sky, and sea, alone and watching the sunset. These concluding character arcs give Frankenstein and his creation slates as white as the Arctic setting, allowing them to embrace nature anew.

In conclusion, Guillermo del Toro’s film, Frankenstein (2025), depicts the mysteries of nature as described in Shelley’s novel, while adding a new twist to Victor’s hubris, by focusing on his family trauma. The director uses actors, colors, and references to Greek mythology in order to enrich his tale, while staying true to the ideas of mankind’s desire to transcend contrasted against the healing power of nature.

Works Cited:

Berg, S. F. “Raw Materials. Half Creatures and Complete Nature in Shelley’s Frankenstein and Homunculus in Goethe’s Faust II.” Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, vol. 14, no. 3, Jan. 2022. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v14n3.09.

Braida, Antonella. “Beyond the Picturesque and the Sublime: Mary Shelley’s Approach to Nature in the Novels Frankenstein and Lodore.” Eger Journal of English Studies, vol. 16, Jan. 2016, pp. 27–43. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=1f6b00f7-64bf-3ce5-8486-c02d8305d978.

del Toro, Guillermo, director. Frankenstein . Netflix , 2025. https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/movies/frankenstein-guillermo-del-toro-transcript/

Hultgren, Neil. “The Museum That Looks Back: Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters.” Neo-Victorian Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 152–81. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=8fb2c27b-2f11-3a0c-a0d8-27ee239bd807.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. Penguin Classics, 2012.

Roche, Hayley Arizona. “Celebrating Imperfection through Perfect Images: Guillermo del Toro’s Work.” SAH: Studies in Arts & Humanities, vol. 5, no. 2, July 2019, pp. 80–93. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.18193/sah.v5i2.184.

Weeber, Rose-Anaïs. “Crimson Peak: Guillermo del Toro’s Visual Tribute to Gothic Literature.” Caietele Echinox, vol. 35, Dec. 2018, pp. 115–26. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.24193/cechinox.2018.35.07.

© 2026 Lou_Summers. All rights reserved